05 September 2025

French corporations are accessing funding at rates below those of the sovereign. Is this justified, or does it point to an overvaluation of their bonds?"

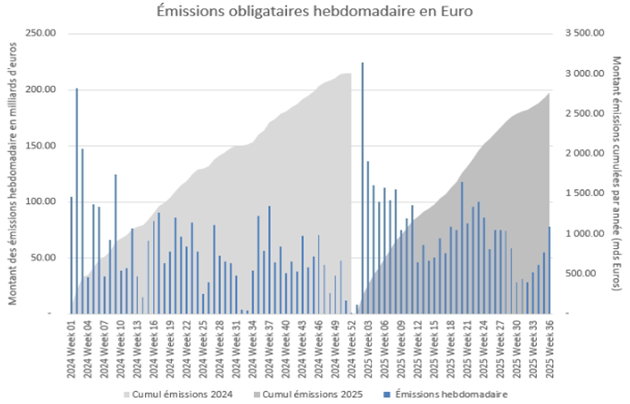

September is traditionally strong for the primary market, and this year is no exception, with record euro-denominated debt issuance, as shown in the graph below.

Source : Bloomberg, Amplegest

Such records are not unusual; they mainly reflect the long-standing trend of bank disintermediation and the refinancing windows common to most corporates—particularly in the investment grade segment. These windows are shaped by uniform bank advice, broadly similar spreads, strong cross-sector correlations, interest-rate moves that affect all issuers, underwriters’ activity cycles, and periods when results are not being published.

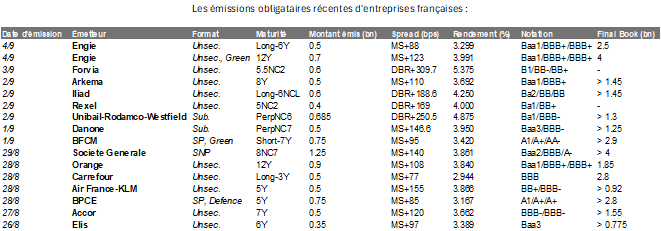

What stands out at the start of this financial year is the strong activity of French corporates—understandable from their viewpoint, but one investors may be better off avoiding.

Source : Bloomberg, Amplegest

We believe investors are not being adequately compensated for the risks of these issuers, who benefit from three structural distortions in the bond market:

- Index weighting by outstanding debt: the more a company borrows, the greater its index weight—irrespective of future risks, particularly political ones, which are rarely analysed and never quantified. In France, where corporate size is polarized between a handful of giants and many SMEs, the largest companies dominate index weightings, and by extension, drive both benchmarked and passive investment strategies.

- Automatic index rollover: indices reflect only current ratings and outstanding amounts. If an issuer refinances just before a major political event or a rating downgrade, the new bonds are automatically included to replace the maturing ones—without delay. Index managers, in turn, must follow suit to avoid creating significant tracking error. This mechanism has often allowed companies—who naturally had better foresight into their own situation than the market—to exploit issuance windows just ahead of negative developments. Some, like Worldline, Wirecard, and Rallye, proved to be unfortunate cases. Others, however, successfully anticipated risks and secured financing on favourable terms.

- An almost systematic lag exists between sovereign yields and corporate bond pricing. Whether sovereign rates tighten or widen, corporate bonds tend to adjust more slowly—largely due to varying degrees of illiquidity. This illiquidity is influenced by factors such as issue size, credit rating, sector, investor base and concentration, the presence (or absence) of derivatives like CDS, subordination, and structural complexity. In short, the stronger the credit component, the greater the latency. For example, a AAA-rated covered bank bond with several billion euros outstanding and a three-year maturity will adjust almost immediately to rate moves, whereas a €300 million hybrid corporate bond may take days or even weeks to reflect the change, as trading flows need time to emerge among investors. This lag has two key implications:

- Active managers can exploit this lag by tilting towards specific bond categories depending on whether interest rates are rising or falling.

- Because this lag effect is directly tied to a bond’s credit component—given that liquidity ultimately derives from credit quality—it must also be evaluated in the context of prevailing credit spreads.

At present, as France’s sovereign credit rating continues to deteriorate relative to its European peers, corporate bond illiquidity is temporarily working in issuers’ favour. As a result, an increasing number of investment-grade companies are borrowing at lower rates than the sovereign itself. Such anomalies usually correct within weeks or months, as institutional investors—by far the largest holders but also the slowest to react given accounting and regulatory constraints—adjust their portfolios through refinancing and arbitrage.

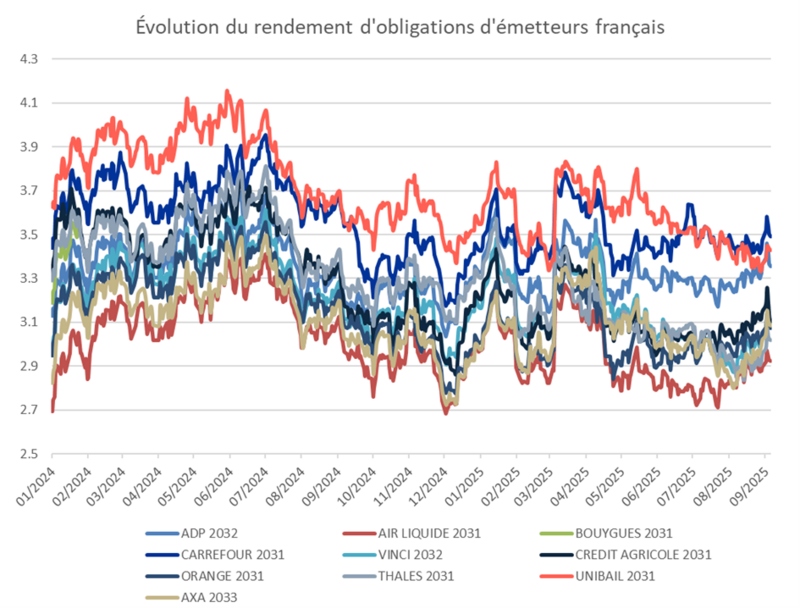

In this context, lending to corporates whose spreads versus the sovereign are likely to correct unfavourably—while sovereign yields are expected to remain under pressure—is not compelling. It risks meaningful relative underperformance, particularly in investment grade, where yields are already modest. History offers a cautionary parallel: during the peripheral crisis of 2011–2014, no Italian or Spanish corporate bond, not even those backed by solid, stable, and non-cyclical businesses, escaped the surge in their sovereign yields. At that time, such bonds represented genuine opportunities because their yields traded well above their intrinsic quality. By contrast, French corporates today sit near their tightest levels (see examples below), offering no premium over their European peers.

Source : Bloomberg, Amplegest

There are two important caveats to this observation:

- Relative versus absolute risk

France is far from the severe crises once faced by peripheral countries, thanks largely to the ECB’s intervention in 2012. This means potential underperformance should be seen primarily in relative, not absolute, terms. For example, a spread widening of just 30 basis points over seven years—entirely plausible in the event of renewed political uncertainty—would translate into a capital loss of around 2%, or roughly seven months of carry on an investment-grade corporate bond rated between BBB and A. In our view, the likelihood of French sovereign yields reaching 6–7% in the short term is virtually nil. However, a yield in the 4.0–4.5% range, versus a European average of 3.5–4.0%, is entirely conceivable. Against this backdrop, lending to issuers such as BNP, Crédit Agricole, Engie, or Gecina—names closely tied to French sovereign risk—at yields of 3.1–3.7% over 7–10 years appears unattractive, especially given the abundance of alternatives in Europe with equivalent credit quality.

- The international profile of corporates

Some issuers, by contrast, have a sufficiently global footprint to partially decouple from French sovereign risk. In the event of a moderate sovereign underperformance (excluding a major crisis), such companies may trade more in line with European benchmarks—or even the German Bund—rather than with French yields. Examples include Air Liquide, LVMH, Pernod Ricard, and Total.

Overall, with a few exceptions, we believe French corporate bonds should be sold—structurally, because of the sovereign’s trajectory, and cyclically, because the lag effect still offers an opportunity to exit at favourable levels.

Matthieu Bailly