17 October 2025

Last week's warning remains in effect for long-term rates

Once again, it was Mr. Trump who set the tone for the markets. Neither the ECB, nor the Fed, nor economic statistics had as much impact as the new trade retaliation measures against China announced last Friday. As usual, the protectionist tone from the US sent instant shockwaves through the markets, causing a sharp drop in equities, pressure on the dollar, and disorderly movements in interest rates. And, as is often the case, this mini-crisis vanished almost as quickly as it had appeared. By the beginning of the week, everything seemed to have returned to their most optimistic levels, buoyed by favorable earnings reports, credit spreads had tightened, except for a few cyclical, high-beta high-yield issuers, and investors had clearly decided that this was just another episode of temporary volatility—a mere repeat of the “mini-crash in April.” It remains to be determined whether this jolt was just another blip, or the first sign of a market beginning to doubt its own invulnerability.

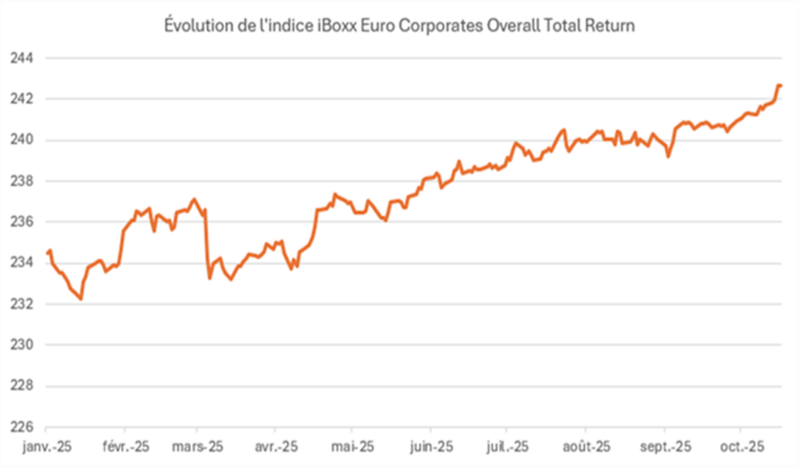

Sovereign bond yields, meanwhile, delivered a signal that has not faded. Both the German Bund and the 10-year US Treasury bond lost nearly 20 basis points in two days, signaling a shift in expectations. The fixed income markets are now pricing in at least two further Fed rate cuts between now and the end of the year, reflecting expectations of a more pronounced slowdown in the US economy and even the possibility of an initial contraction in the labor market. This is not yet a recession scenario, but rather one of a gradual slowdown that would justify a more accommodative monetary policy. Spreads initially widened but then quickly returned to normal, while rates tightened significantly. Ultimately, the bond market became even more expensive, as shown in the chart below representing the European corporate bond index. Stocks are returning to their highs, but so are bonds, indicating that investors are not worried but are not overly optimistic either. Rather, it shows that they have confidence in their monetary institutions and are relieved in anticipation of the central banks' assurances of vigilance and potential further rate cuts... And we won't even mention gold, which is also sending a clear signal of mistrust in the economy, monetary and financial stability, and central bank balance sheets...

Source : Bloomberg, Amplegest

Focusing on Europe, France continues to stand out, and not for the right reasons, with its spread widening further each week compared to the European average. The country is set to break a new record for sovereign bond issuance this year, against a backdrop of political uncertainty and the absence of a credible budgetary trajectory. The markets would have liked to see a sign of control over public finances ; instead, they have been left with an institutional vacuum. In this context, French risk remains unattractive, not because France is in acute economic difficulty, but because its budgetary policy inspires little confidence. While these budgetary wanderings and risks on sovereign rates should have little or no impact on large French international corporates – LVMH, Sanofi, Air Liquide – whose real exposure to France is marginal and whose performance depends much more on US or Chinese demand than on French growth. Domestic players, on the other hand – banks, utilities, infrastructure – remain the most exposed to fluctuations in the government's credit rating, and we continue to avoid them carefully in favor of their European counterparts.

Finally, a word about Switzerland, where the Credit Suisse-UBS saga has entered a new legal phase. The Federal Administrative Court ruled that FINMA had violated the property rights of AT1 bondholders when their bonds were written down to zero in March 2023. This is certainly a resounding decision, but one with limited consequences for the time being: it recognizes an infringement without imposing financial compensation, which does not seem so easy. It is hard to imagine UBS, which took over Credit Suisse at the request of the authorities, having to compensate the creditors of its predecessor in capital, at the request of the same authorities... It is also conceivable that the principle of liability guarantee, which covers losses for reasons already proven prior to the transaction and which applies to the smallest buyback transaction between two SMEs, also exists in the transaction between UBS, Credit Suisse, its shareholders, and the Swiss government or FINMA... It is therefore unlikely that the penalty will be very costly for UBS, and the markets have hardly penalized the Swiss leader's shares or bonds. For most AT1 holders too, some of whom may be tempted to boast these days that they have won their case, let's not forget that most of them bought these bonds at 100% and will only be able to recover a few euros... The big issue in the proceedings was the reversal of the unsecured ranks, meaning that shareholders received $3 billion for their shares, while $16.5 billion was wiped out for AT1 creditors. Assuming that the former shareholders return the entire €3 billion that remained of Credit Suisse's total value, creditors would therefore be able to obtain a maximum of 18% of their investments, before any procedural and settlement costs. (3/16.5) One could also imagine UBS issuing perpetual super-subordinated instruments for the amount owed, which could compensate investors' losses without forcing UBS to pay out cash immediately and allowing it to smooth out this compensation over a long period of time, or even reserve the option of never repaying them. Since banks always need capital and additional subordinated debt instruments, this type of formula would not be particularly penalizing.

Ultimately, assuming that investors recover between 15% and 20% of the nominal value after more than two years of proceedings that are likely to be relatively costly, only a few specialized funds that purchased Credit Suisse debt close to zero once the transaction was announced and in the weeks that followed, with the sole objective of pursuing these legal proceedings, will actually make a substantial profit. For the others, most will have lost at best 80%, and probably a little more, instead of 100% of their investment... This procedure, which could simply push the authorities to improve their regulations and refine their wording in order to allow themselves as much room for manoeuvre as possible and avoid future actions of this kind, will therefore ultimately have only a very modest impact, if any, on the UBS-Credit Suisse transaction itself.

Matthieu Bailly