12 December 2025

Carry and time matter more than force or fury

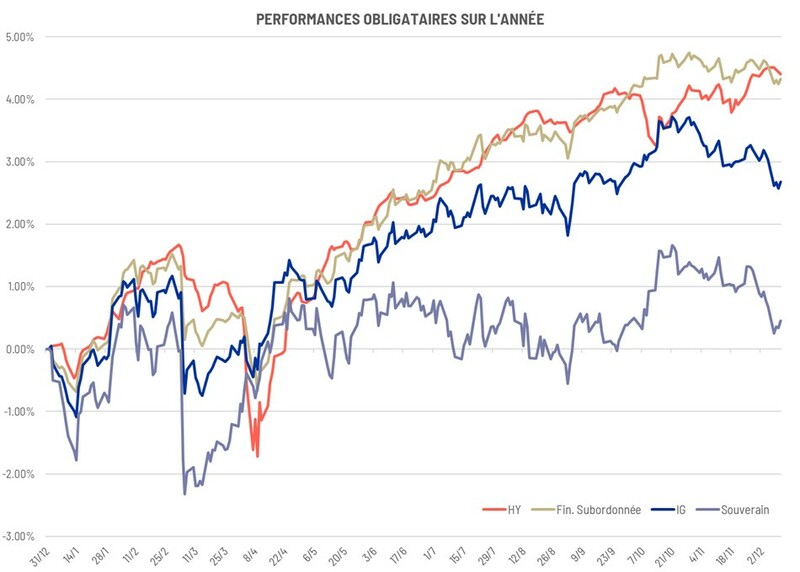

2025 is coming to an end without any real surprises. Returns are very close to the annual carry, in a context marked by the absence of major incidents in the credit markets – apart from the brief episode in April, when it was preferable not to alter one’s initial allocation – and by generally contained volatility. This configuration serves as a reminder of a reality often forgotten: when spreads remain stable and rates move within relatively narrow ranges, bond performance is essentially mechanical. In Europe, Investment Grade bonds posted returns close to 3%, while High Yield bonds delivered around 5%, exactly like subordinated financials – levels consistent with the yields offered at the start of the year. Sovereigns, however, once again provided zero performance to their investors, as their carry remains low, their average maturities – and therefore their sensitivity – are generally much longer, and their fundamentals and drivers of change remain highly unfavorable, ranging from fiscal imbalances and central bank balance sheet reduction to the gradual disengagement of international investors. And this could well continue next year, unless a major crisis were to prompt the ECB to cut rates and investors to engage in a flight to quality... Yet can French debt still be considered “quality”? Nothing is less certain, especially if the major crisis does indeed occur, which cannot be ruled out... In that scenario, Spanish, Italian, or Greek bonds, along with gold, might well outperform other European sovereigns such as Germany or France, even though the index below is mainly composed of the latter two issuers, since it is weighted solely by the volume of debt outstanding.

Sources : Bloomberg, Amplegest

Credit markets remained remarkably stable. Companies, particularly in Europe, continued to act cautiously in the face of persistent economic uncertainty, while investor demand stayed firmly anchored in corporate credit—even though a significant portion of portfolio turnover shifted toward equities or riskier assets in search of higher expected returns. European sovereign bonds, by contrast, remain the poor relation in asset allocations: still-low yields, notable volatility, and latent fiscal risks make the risk/return profile unattractive, especially at longer maturities, despite the catch-up seen again this year. By contrast, we continue to keep US Treasuries in mind (see weekly note of November 21, 2025). With their higher yields (unhedged for currency risk), the government’s far greater fiscal flexibility, and the country’s economic and political strength, they appear to offer a valuable source of protection in portfolios against the risks looming in 2026.

On the central bank front, the main source of uncertainty remains in the United States. In Europe, the situation is unfortunately all too clear: the ECB has already embarked on rate cuts, and the European economy, stuck in structural stagnation, leaves little doubt that rates will stay low. The only real point of tension lies in long-dated sovereign debt, where spreads—particularly for France—could continue to widen over time, reflecting an increasingly blurred fiscal trajectory. In this environment, short- and medium-term maturities, and corporate bonds in particular, remain the preferred allocation in the eurozone. In the US, the picture is more nuanced. Rates are materially higher, fiscal flexibility is more tangible, and the Fed has not yet fully completed its easing cycle. The US central bank has recently resumed short-term asset purchases to maintain sufficient liquidity in the system—a move presented as technical but which, in practice, amounts to an additional injection of support. In this context, holding some US Treasuries in a portfolio appears sensible : the carry is attractive, and in the event of a more accommodative monetary policy, prices could benefit just as much as they would under major stress, which has not been seen for some time. Financial markets, however, tend to follow relatively regular and statistical cycles...

The end of the shutdown and a degree of fiscal normalization are also providing greater visibility. As in his first term, Donald Trump alternates between headline announcements and subsequent reversals, ultimately creating a kind of political routine. Markets have adapted: reactions are now more measured, less emotional, and the volatility linked to US announcements has gradually diminished.

In Europe, the divide between the south and the north continues to deepen. Greece, now at the helm of the Eurogroup, embodies a spectacular economic recovery after a decade of painful reforms. France, by contrast, remains mired in difficulties: a lack of clear political direction, steadily rising public debt, and anxious households saving more while consuming less. These savings, though abundant, may provide short-term financing for the state, but over the longer run they foster economic inertia, which is hardly conducive to stronger tax revenues or meaningful deficit reduction.

Finally, at the microeconomic level, companies remain true to their habits. Credit requires a long memory, and that is often where the difference lies. The recent example of CMA CGM is telling: the quintessential opportunistic issuer, the group knows how to seize market windows. Its latest convertible bond, carrying a 0.5% coupon, perfectly illustrates its ability to secure financing on terms extremely favorable to the borrower. While we remain confident in the group’s overall strategy, this type of instrument clearly appears unattractive for bond investors: a yield close to zero, a relatively cyclical issuer, and convertibility into an underlying asset that is itself highly volatile, unreliable, and facing relatively unfavorable macroeconomic and idiosyncratic prospects. Air France, which compared to CMA CGM sits firmly at the opposite end of the spectrum, has been regularly downgraded due to its heavy-handed operational and financial management. Alongside names such as Atos, Worldline, or even the French government, it illustrates precisely what we seek to avoid: erratic management and a steady deterioration in credit risk. History is also repeating itself at Altice which, after an already heavy restructuring, is once again attempting to impose concessions on its US creditors. Casino had taken the same path only a few months earlier.

Sources : Bloomberg, Amplegest

These examples remind us of an often-overlooked truth: credit is built above all on trust, and trust is forged over many years, even decades. Notable examples of financial reliability include companies such as Schneider and Air Liquide, or, in the inherently riskier LBO sector, firms like Loxam. Since its creation in 1967, its first LBO in the 1990s, and the multiple refinancings that followed, Loxam has never defaulted on its creditors and has consistently demonstrated sound management, the robustness of its business model, and remarkable adaptability to the numerous crises it has faced over time.

More than current figures, it is the long-term reliability of an issuer that should guide bond investors.

Matthieu Bailly