23 May 2025

Warnings about long-term interest rates are being repeated around the world.

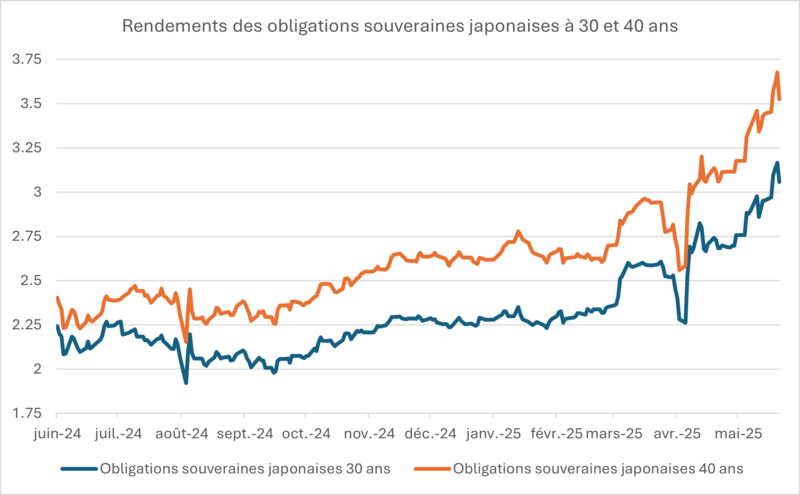

While the consensus continues, tooth and nail, to bet on significant rate cuts by central banks driven by falling growth, falling inflation and an accommodating stance to “preserve the system”, signals of rising long rates continue to accumulate around the world, bringing disappointment after disappointment to this bet... So, after the upheavals in US and European long rates in recent months, it's now the turn of Japanese long rates to jump in recent weeks, particularly on maturities of over 20 years, as the graph below shows.

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg

After the fact, all analysts will find justification for this, whereas a few weeks ago there were countless articles explaining that Japan was a special case and that its rates were particularly attractive at 2.5% on 30-year bonds... It's not the first time, and our regular readers may resent us repeating ourselves, but isn't it usually said that the bond pocket of a portfolio is the safe part of a portfolio, dedicated to providing coupons, limiting volatility, and offering visibility on capital?

Is investing in government bonds with a maturity of more than ten years, which are structurally in deficit, for yields of 2% to 3%, while short-term investments offer 3% to 4%, really in line with the portfolio's risk-reducing bond vocation? We don't think so, and unless they meet regulatory or asset/liability management constraints, or represent a tiny proportion of the portfolio to hedge a specific risk - which is the domain of a few specialist investors - we consider long positions in these government bonds to be risky and eminently speculative for most investors with a 3-5 year investment horizon and a yield or volatility objective of 3% to 5%.

In our view, these jolts in long yields are not opportunities, but harbingers of long-term pressure on this segment of the curve stemming from:

- The persistence of higher inflation than in the past in all “developed” countries, between trade tensions driven as much by budgets as by geopolitics, the enrichment of emerging countries, bottlenecks in raw materials or technology, and social tensions pushing for long-term wage increases.

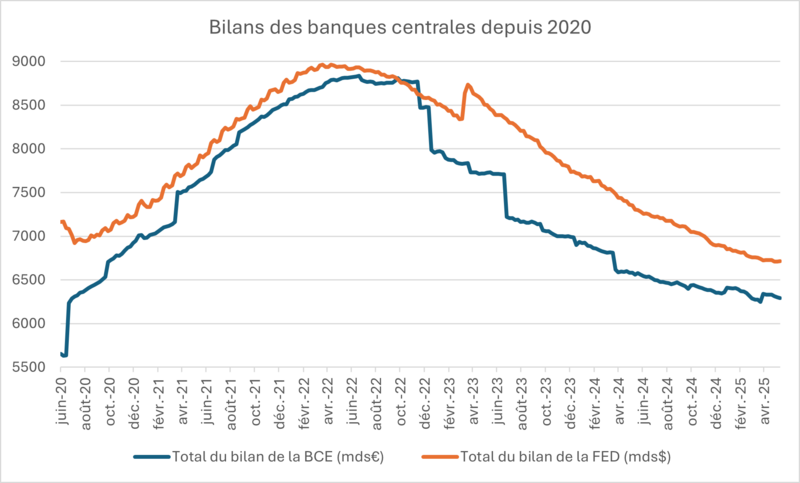

- The maintenance of a more restrictive balance sheet policy by central banks, leading to a reduction in their purchases of sovereign bonds. The case of the Bank of Japan in recent months is an illustration of this, as has been the case for the FED or the ECB since 2022. (see graph below)

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg

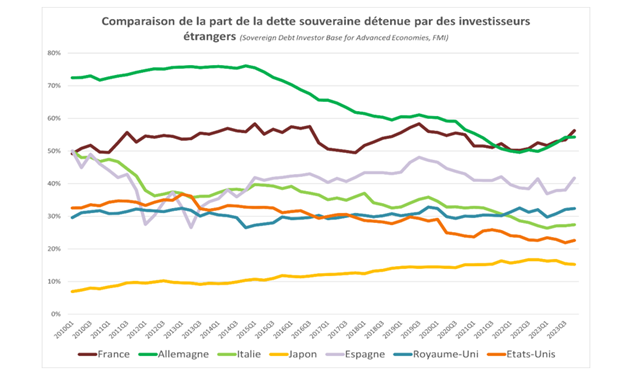

- The relative increase in the credit risk of traditional safety-net countries (Eurozone, USA) vis-à-vis emerging countries, coupled with the bipolarization of the world: in short, Eurozone countries and the USA will benefit from a smaller pool of investors in the future than in the past, for three reasons, independent or combined as the case may be:

- Outright deterioration in the credit quality of historically reliable regions: relative impoverishment, rising debt levels, falling currencies (Eurozone, France)

- Geopolitical breakdown or tension limiting foreign investment (Russia or China)

- Improvement in local credit, enabling domestic investors to secure their assets locally rather than in other regions (e.g. India).In this context, it is likely that those countries currently most dependent on foreign investors for the placement of their sovereign bonds will suffer more than those relying on their domestic investors, whether institutional or private savings, and that countries with sluggish growth and the lowest rise in purchasing power will be at greater risk than countries with stronger growth dynamics.

In this context, we would particularly warn against sovereign debt in the Eurozone, which is the most heavily held abroad and the least economically dynamic, while Japan and the USA benefit from a stronger local base, and the latter regularly return to growth phases capable of reducing their indebtedness or increasing the mass of savings. Within the Eurozone itself, we will remain extremely vigilant with regard to France, which we have been limiting to the smallest possible portion of our portfolios for almost a year now, and in respect of which we do not hold any government bonds, as it combines all the above-mentioned risks for a premium that is still virtually non-existent.

Sources : IFRAP, FMI

From the point of view of interest-rate risk, we therefore prefer to position ourselves on a relatively short time horizon in view of the possible upward pressure on rates, and hence downward pressure on the bond market. But from a credit point of view, is the same true, or are corporate premiums and corporate visibility good enough to position ourselves on long credit?

We won't go back over credit premiums here, which were the subject of our last weekly report and for which we concluded that they remained relatively tight.

From the point of view of visibility, which the clearer it is, the more attractive it is for long-term lending, the current economic climate is anything but clear-cut, and while companies remain, on average, quite reliable from the point of view of their balance sheets, their outlook is very cautious and generally does not give much precision on their medium-term figures, so low is their visibility from all points of view: economic, political, commercial, geopolitical... This week, for example, in the course of the various earnings presentations we have been able to consult, we will note in particular in terms of outlook or growth among issuers on the corporate bond market: disappointing guidance from VF Corp, growth well below target at Elior, slower growth at Iliad, stable sales at Hornbach, lower sales and earnings at Biogroup and Cerba, stable outlook at Rekeep, stable earnings and slight growth for 2025 at Sunrise, great caution from CMACGM on its outlook announcements for fiscal 2025 even though we're already halfway through the year... In short, we do not blame any of these companies for their uncertain situation, but they do confirm our cautious stance on credit:

- Solid balance sheets in terms of cash flow, enabling serene investment over an average 2–3-year horizon

- Low visibility and relatively weak sales and earnings trends which, at best, do not point to any improvement in credit ratios and could be a source of deterioration in the event of unforeseen events or a tougher economic cycle.

As a result, we feel that interest-rate equilibria are in line with credit equilibria, and that our positioning on these two vectors of bond performance is rather short. Only the banking sector, after a decade of regulatory moult and interest-rate dearth, is currently enjoying a relatively lasting upturn, and combines three advantages for a creditor: - Solid balance sheets, closely monitored by regulators, especially in Europe,

- Good visibility on activity and credit ratios, particularly for network banks, the institutions we almost exclusively favor in Octo portfolios.

- Credit premiums that are still attractive relative to corporates, especially on subordinated bonds, which are more complex and less present in aggregate bond indices.

These advantages of bank and insurance debt justify an overweighting of financial bonds (excluding real estate) within a bond portfolio, as demonstrated by the positioning of the Octo Crédit Value fund for several months now (50% financial bonds in the portfolio).