13 June 2025

Ciao Francia: Italy becomes better student than France...

On the bond front, one week follows another in relatively monotonous fashion: Credit spreads are stagnating at their lows, curves are tending to steepen again, sovereign yields are crystallizing uncertainties but are not yet really diverging, and investors are sticking to the positions they have built up over the past few months, with arbitrages between bond categories for a few basis points not really worth the effort...

So it's hard to offer you new bond opportunities every week, but it's more like the same little signals which, if they don't cause any stir or particular emotion among investors, are gradually accumulating and will have a significant impact in the long term: firstly, on relative spread between issuers; secondly, on systemic risk, as the subject of interest rates and sovereign risk takes on greater importance; and, finally, on possible new quantitative easing by the ECB and/or the Fed.

This week, we'll take note of four recent parallel news items, signalling what we believe to be a major trend in European sovereign debt: Italy's credit quality will soon be better than France's, making the latter the riskiest country in the Eurozone.

- Italy's credit rating raised to BBB+ by S&P (Les Echos)

- Moody's rating agency refrains from rating France (BFMTV)

- While France is mired in deficit, the IMF congratulates Italy on its budget surplus (BFMTV)

- Italy's GDP per capita reaches that of the French (Les Echos)

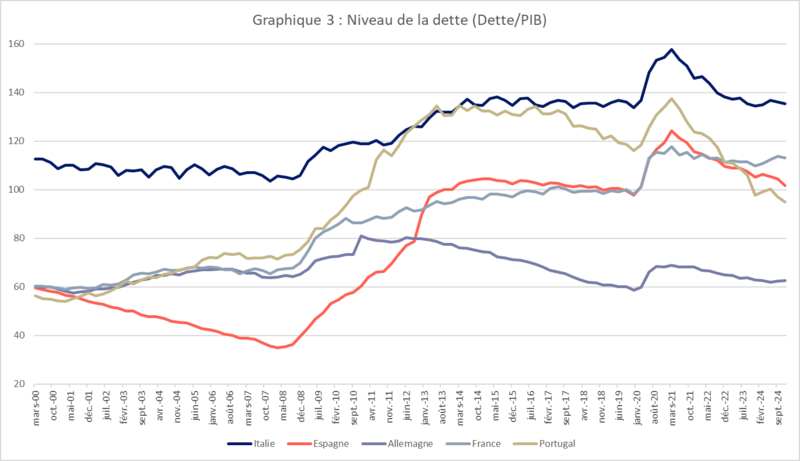

For the past fifteen years or so, advocates of “French credit quality” had always found examples of other European countries, either more indebted, or with larger budget deficits, or economies more dependent on this or that, or with more unstable political systems, or with greater corruption, or, or, or.... Sometimes it was Greece, sometimes it was all the peripheral countries, sometimes it was Portugal, and very often it was Italy, which until a few years ago remained the Eurozone's bad pupil, the one that ensured France's place in the pack... A pack of dunces, to be sure, but an undistinguished pack, which the ECB held at arm's length thanks to its liquidity.

In the last few months, with Italy's major budgetary and economic efforts, the bad pupil also seems to have returned to a healthier budgetary trajectory, like Portugal, Ireland, and Spain in their day, and could, like its peers, begin to improve its public finances, while France seems to have lost all control.

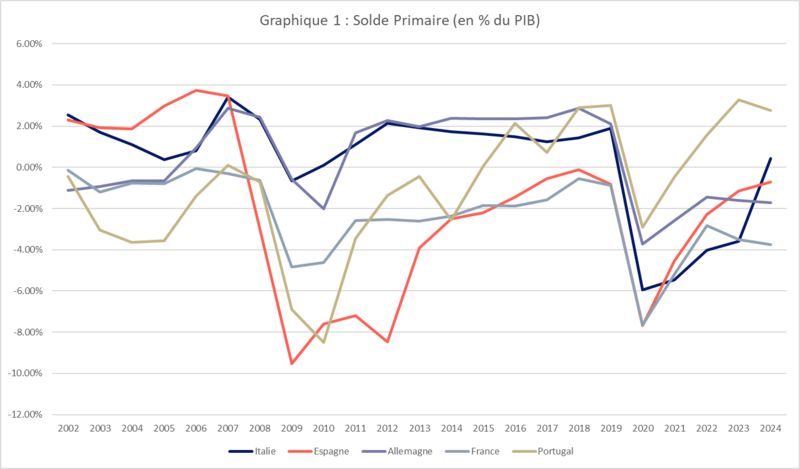

To reduce its debt, a country that has been through a difficult period generally undergoes two preliminary stages, the first of which Italy has just achieved: a positive primary budget balance.

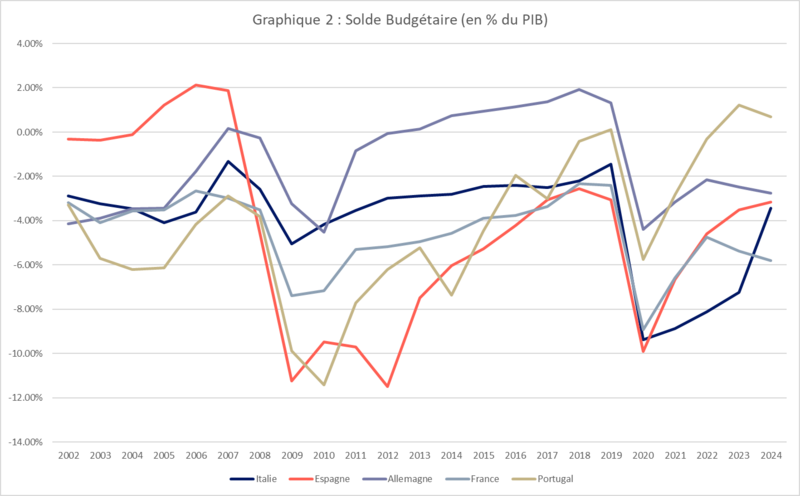

A government budget is made up of two parts: expenditure on public services and interest on borrowings or “debt charges”.

The primary balance excludes debt servicing costs and is used to determine whether the “operational” part of a state’s budget is in balance. In other words, whether, apart from interest on debt contracted in the past to resolve past problems, a State is in balance in its management of the present. This positive primary balance is crucial to a country's fundamental credit analysis, as it offers two possible tools for debt reduction:

- The first is gradual and classic: the central bank, by lowering rates in line with the trend, can allow interest rates to fall progressively, creating a virtuous spiral of credit improvement and hence reduced spreads and borrowing rates, and ultimately making the budget balance positive, which leads to debt reduction. Conversely, a fall in interest rates in a country that needs to borrow to support its lifestyle will, at best, serve no purpose, and may even be a spur to crime for certain governments who see it as free money...

- The second is not used because it is violent, but it is a considerable asset in the hand of a State with a positive primary balance in its relationship with creditors: debt write-off! But why would a government be foolish enough to scare the markets so much? Quite simply because it no longer needs to. To simplify the concept, let's take two examples:

- State A suffers from a negative primary budget balance and an insurmountable stock of debt. It may well find it tempting to unilaterally write off its debt to get back on its feet, but this will have two consequences: 1/ its credibility on the markets will become nothing, and 2/ its borrowing rate, should the need arise, will be extremely high. By definition, a state with a negative primary balance will immediately need to borrow again to pay for its public services. This debt write-off, the ultimate threat to bond investors, will be totally pointless and counterproductive.

- State B has a positive primary budget balance and an insurmountable stock of debt. It may find it tempting to unilaterally write off its debt to get back on its feet, and this will have the same consequences: 1/ its credibility on the markets will become nothing, 2/ its borrowing rate, should the need arise, will be extremely high. However, since State B will no longer have to pay interest and will have a positive budget balance, it will not need to borrow and will therefore be able to cut itself off from the financial markets without any consequences for its operations. Although this weapon is never used, it was nevertheless often put forward in the 2010s as a potential temptation for countries like Portugal, which had made extremely heavy budget cuts and might have found it politically and socially legitimate to reduce its debt to preserve its population, which had become exsanguinated.

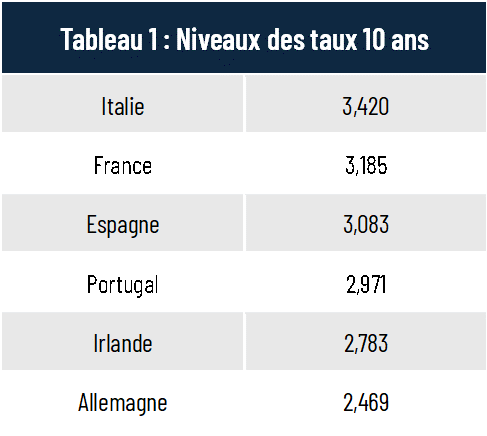

A positive primary balance, because it opens the door to interest relief, renewed economic dynamism and a rebalancing of terms of trade with creditors, is generally the prelude to a country's debt reduction and improved credit quality. This has been the case in Portugal, Ireland, Spain and now Italy (see Charts 1, 2 and 3), while France remains mired in a primary balance deficit. While Italy's stock of debt is currently greater than France's, and its borrowing rate even higher, we can imagine that the hierarchy will be reversed in the years to come, as has already been observed for the other ex-peripheral countries. (see Table 1)

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg, Eurostat

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg, Eurostat

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg, Eurostat

Sources: Amplegest, Bloomberg

France is therefore on a fairly straightforward absolute and relative downward slope in terms of quality and credit premium, and we are continuing to carefully avoid the French government and corporate bonds with too strong a link to the French government or economic situation: banks, insurers, utilities, energy, public or semi-public companies, local authorities, companies with too little international diversification, in particular a large proportion of French SMEs in the local market, a category virtually absent from the traditional bond market but which can be found in “private asset” funds.

Let's not forget, either, that France is the Eurozone's second-largest economic power, and that this downgrading will probably also have an impact on the overall credibility of the Zone, as many international investors, led by emerging countries, who have traditionally invested in it to secure their capital, may gradually turn away, considering that the driving force and improvement of the ex-peripheral countries will not be sufficient to compensate:

- Either to the benefit of other zones, including their own countries; emerging countries' credit quality and emerging currencies should strengthen significantly against the Eurozone and the Euro in the coming years

- Or to other assets, notably gold, as illustrated by this article from Agefi dated June 12, 2025, which notes that gold has overtaken the Euro in central bank reserves.

Mattieu BAILLY