07 March 2025

Our bond viewpoint on the German investment plan and its consequences

At the start of the year, when we carried out our traditional bond outlook roadshow, we were astonished by the fact that most analyses, articles, and interviews mentioned a host of risks, whether macro, political, geopolitical, or economic, but that nothing showed up in flows, valuations or allocations,

- We heard or read that the curve was set to steepen but remained imperturbably flat.

- That credit spreads were becoming relatively tight in certain segments, but were continuing to tighten

- Mr. Trump's initial measures would be unfavourable to world trade and growth, but equities continued to climb

- Germany's difficulties were mounting, but the Bund remained virtually unperturbed by other European countries.

This was merely a latency effect for the markets, caught between their traditional optimistic bias that all assets should always rise, even if some are inversely correlated, and the reality that was knocking at the door. All things considered - and we hope it will be much less - this phase is reminiscent of the first few weeks of the Covid episode, or those of the war in Ukraine: the event and the conditions are in place, but the spark is missing for everything to get off the ground...

The spark did in fact come this week, and it was our German friends who lit it, with news that has the specificity of being rather positive in the long term for the economy, but rather negative in the short and even medium term for the financial markets and for the valuations of a good number of assets. Given the stakes, the time horizons and the eminently political issues involved, rather than taking a firm and definitive position on the subject, in this issue we will attempt to sketch out some of the short- and long-term consequences of this German event on the markets, particularly bond and credit markets.

But for those of you who don't know exactly what we're talking about, let's start by clarifying the subject, which may seem quite positive at first glance: Germany, spurred on by the rest of Europe for several years and by its difficult economic situation in recent months, has in fact just announced its willingness to break the lock it has held firmly shut for decades: that of indebtedness.

Of course, we can't expect Germany to follow in the footsteps of its French counterpart, and an accommodating German spending policy is likely to be a throwback to the French government's most restrictive period in decades! But this announcement, if followed by action, should have several impacts:

- Accentuate and accelerate the steepening of the European yield curve, mainly through a widening of long rates.

- Keep bond yields durably high

- Provide support for the euro against other world currencies, led by the dollar

- Narrow the interest-rate gap between certain ex-peripheral countries and Germany

- Relaunch and strengthen European collaboration on subjects that are still difficult: Eurobonds, joint budgets, major projects, financing the energy transition, etc.

- Encourage the ECB to pursue its policy of lowering interest rates

- Create an extremely volatile bond environment over the coming months

- Increase the risk and therefore the premium of the Eurozone compared to its peers, because before the stimulus can bear fruit, deficits, debt and execution risk will have to rise.

- Maintain negative pressure on interest-rate-linked valuations, led by real estate, but also low-yielding equities that are little affected by a relatively targeted stimulus policy.

After these general considerations, let's go into a little more detail with a few questions we've received over the last few days:

- How high will Germany's debt level be?

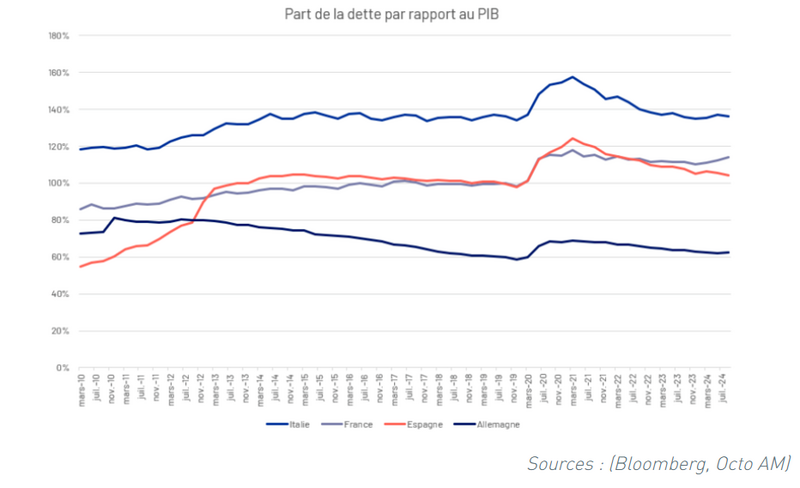

Germany's current debt level stands at around 64% of GDP, well behind France and Spain's 112% and Italy's 135%, giving it a comfortable margin for manoeuvre that many observers and politicians were urging it to use to revive the European economy. If we consider that this policy could be spread out over a decade or so, given the typology of projects put forward by the new government - defence and infrastructure - Germany's debt-to-GDP ratio could approach 80 to 100%, i.e. the level of France during the 2010 decade.

In terms of amounts, German debt could increase by between €1,500 and €2,000 billion over the next ten years, which is a significant amount for the Eurozone as a whole since it is the equivalent of Spain's current total debt.

- Is this plan good for bonds?

Bond valuations can react to two different issues: rates and credit.

In terms of interest rates, this type of targeted stimulus plan would tend to increase growth and inflation potential in Germany and the Eurozone over the medium term, thereby pushing up the Zone's equilibrium rate and driving down bond valuations. It should be noted that, to date, this vector remains relatively weak, as its effects: 1. will be visible more in the medium to long term; 2. could be targeted on a few sectors or a well-defined geographic zone; 3. remain subject to execution risk. For the time being, therefore, the perceived impact on interest rates seems limited, and more related to the degree of optimism of an observer than to any concrete reality.

From a credit point of view, on the other hand, because the spending is likely to go ahead, whatever the outcome, the impact is clearly negative both for a direct creditor of Germany and for a European bond investor in general on several levels:

- Germany's credit quality is entering a downward slope, which should increase its credit premium.

- The credit premium of the Eurozone in general, because its safest and most orthodox country in terms of fiscal policy is taking the risk of tipping over to the side of the southern countries, is likely to diverge as well.

More generally, higher yields can be expected for longer across Europe because of this decision, which is not particularly positive for short-term valuations, but does offer the prospect of more sustainable investment in the bond segment.

- Is it good for corporate credit?

In addition to its interest-rate and sovereign credit components, corporate credit has an intrinsic credit component, and it is conceivable that a massive investment plan could be relatively positive for the economy and therefore for companies. There are several nuances to this observation:

- The investment plan is relatively focused on defense and infrastructure, as well as on Germany, and will therefore, in the first instance, affect only a small portion of the European business fabric. Here, we can recall the 2010 decade and Germany's economic exceptionalism compared to its Eurozone counterparts, which continued to struggle despite growth on the other side of the Rhine regularly hovering around 2%, which is the current target for the coming years.

- The plan will begin with national debt, which will be used to place orders with companies, who will have to invest to meet these orders and increase their production, thereby creating said growth. From a credit point of view, therefore, we know that spending will be certain, but execution and results less so, and the heavier the investments, the greater the risk. While this plan may therefore be beneficial from a long-term economic point of view and have a positive effect on the credit of certain sectors such as infrastructure, once the benefits have been reaped, it will bring additional uncertainty to corporate credit and spreads in the short and medium term.

- While some companies will quickly see their order books fill up, most others will only see positive effects after a few years of this plan and will in the meantime have to bear potentially higher financing costs due to rising interest rates and the immediate and certain rise in the European risk premium. With credit spreads already at levels close to their lows, such a change in economic equilibrium is a source of additional credit uncertainty and caution for bond investors.

- What slope should we aim for?

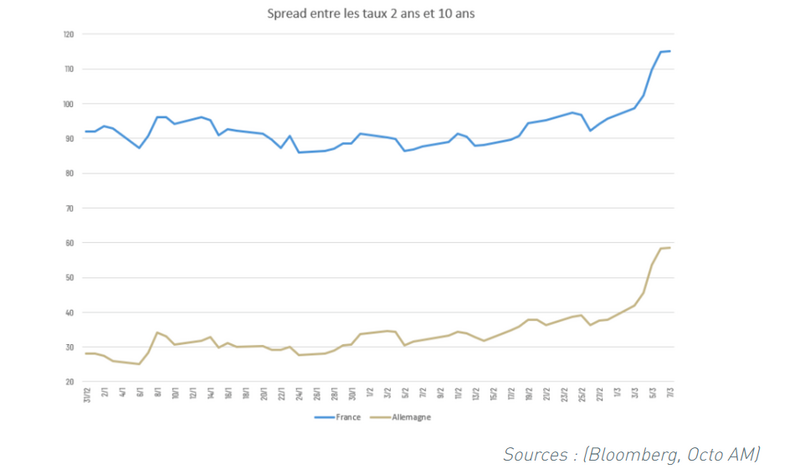

Since 2023, we've been saying repeatedly that the slope of the curve was too low and did not adequately reward long-term risk: why lend to a company or a government at 10 years at the same rate as at 1 year, when the risk is much higher, we used to say. This week's event in Germany is a very concrete example of what we feared by keeping investment maturities rather short. The credit quality and solvency of a government or company is perfectly measurable at one or two years, but becomes much more uncertain at 10 years, and this uncertainty needs to be remunerated. It wasn't, but it clearly has been for the past few days, with a slope that has steepened significantly (see graph below).

The average slope of a country like Germany or France over a long period is between 100 and 150 basis points between the two-year and ten-year maturities, i.e., an investor is remunerated with 1.5% additional yield each year for lending at ten years rather than two years. At a time when Europe's most important country will be borrowing massively on a long-term basis, creating a significantly unfavorable supply/demand effect, and adding additional risk to the entire zone, we consider that the slope of the curve should largely reach its historical level, and is unlikely to do so in a smooth and orderly fashion. It would therefore be entirely possible to see a steeper slope on two occasions: either in the coming months, due to the volatility associated with the uncertainty of this policy change, or in the longer term, as the entire Eurozone approaches the situation of the peripheral countries in 2011-2012...

- Should we switch to government bonds?

In the very short term, we'd say no, unless you're subject to insurance-type constraints, between maximizing the purchase rate, avoiding mark-to-market and improving the SCR and yield/SCR ratio. Indeed, the trend is likely to resemble that of 2023 and 2024, with a hint of additional volatility, all for yields that remain moderate.

However, volatility and rises in government yields are such that significant arbitrage or portfolio switching opportunities could arise for bond investors. Indeed, in recent days, as in 2022, the fall in valuation began with interest rates without immediately spreading to other asset classes, notably credit, which had the immediate effect of tightening spreads. For example, these days we're seeing a significant narrowing of a subordinated Generali bond relative to its benchmark, Italy, simply because of a time lag and lower liquidity: does it make sense for a 7- or 8-year subordinated Italian insurer's bond to offer just 0.5% more annual yield than its benchmark country? We don't think so, and against this backdrop of high volatility, it will be advisable to carry out regular portfolio reviews to check that the risk/return ratios are all legitimate and, why not, make a few switches, towards government bonds, the first to see their premium currently diverge.

- Will Germany remain the European benchmark? Back to the notion of the European average rate.

We have often defended the notion of the European average rate for portfolio management and monetary policy analysis. Indeed, if Germany was always taken as a benchmark by investors, it was only because, at that precise moment in time, it had the lowest rate in the zone, and because its credit risk was the lowest in the zone. However, as mentioned above, credit risk is a moving target, and there is no guarantee that Germany will remain, ad vitam, the least indebted and least risky country in the Eurozone. What's more, the ECB, in its outlook, its choice of key rates and its government bond purchase and sale programs, includes all Eurozone countries, not just Germany, which is what makes it so difficult to compete with the FED... Although Germany is likely to remain the European benchmark for years to come, we nevertheless believe that the phase now beginning should accentuate the phenomenon of tightening and homogenization of European rates: the first phase, post-crisis in the peripheral countries, was a tightening of peripheral rates against the German benchmark; the current phase will see a widening of the German credit premium against its peers.

The problem for a European investor is that the notion of a risk-free rate or “reference rate” is in fact fluid, relative and linked to equally fluid subjects: his or her own country, the country of the issuer being analysed (remember that many European banks benefit from rating notches linked to their country), the hierarchy of European countries at specific time, etc.

To counter this problem, we consider it preferable for an investor to restate each credit spread against two different benchmarks:

- His own country's rate, particularly for certain issuers closely linked to country risk: banks, insurers, infrastructure, energy, etc.

- The European average rate, represented, for example, by an average of local rates weighted by GDP or debt mass, which enables us to maintain a more stable benchmark over time, limiting the credit risk of any given country, with Germany in the lead in the current context of a probable widening of its credit premium compared to other countries.

- Can the stimulus plan jeopardize the ECB rate cut?

While such a plan could, in the long term, increase the outlook for growth and inflation, and thus prompt the ECB to revise its equilibrium rate outlook upwards, it will not call into question its current policy and its quasi-commitments to rate cuts, for three reasons:

- Not to add volatility to an already extremely volatile environment

- To avoid making Germany's future borrowing on the markets more difficult and costly, at a time when the country is announcing a plan that could revive Europe.

- Don't take at face value a plan that has only just been announced and not yet adopted, the effects of which will only be seen in the medium/long term.

In conclusion, while it is difficult and dangerous to switch portfolios in a bond market as volatile as this week's, the current movements stemming from a rather unexpected political statement by the future German government - but it could very well have been something else, given the many uncertainties currently facing the world and Europe in particular - , which are likely to affect credit, interest rates, the economic outlook, certain sectors rather than others, monetary policy, sovereign risk and the slope of the curve, you'll need to remain extremely agile in your management:

- flexible, opportunistic bond management rather than fixed-term funds, except in specific cases of liability matching

- use liquid assets rather than closed-end funds to achieve this flexibility

In terms of bond allocation, we will continue to advocate a cautious approach to credit, given the tight premiums and ongoing uncertainty, and to keep duration rather short. As mentioned above, we should also bear in mind that country risk could return in the months and years ahead in Europe, and that it is therefore preferable to take position

- either on corporates that are as free as possible from this risk, which is extremely complex for investors to manage (as the crisis in the peripheral countries and the subsequent restructuring of Greek debt clearly demonstrated)

- or on the most favorable countries in terms of risk/return ratio at specific time and in trend, more specifically in exposed sectors such as financials: in this case, for example, we prefer Spanish banks to German ones. As for France, the most troubled European country at present, we have limited our exposure since June 2024 to the smallest possible portion of a portfolio, e.g. around 5% on our Octo Crédit Value fund, compared with around 30% for most bond indices.