10 January 2025

The widely-publicised plebiscite in favour of the new sovereign bonds is nothing more than a crude deception that we must not fall for!

The start of the year is traditionally a busy time for the primary bond market, and this year shows no exception, with a particular focus on sovereign bonds, as European governments are set to issue record amounts of bonds in 2025 to finance their persistent budget deficits... led by France...

As the year has just started only six days ago Eurozone governments and government agencies have already issued 42 new bonds worth more than €800 billion, up 30% on 2024, which was not a year of restraint in terms of budget deficits and therefore government debt! While the investment banks in charge of these investments are happy to use superlatives, already seeing their commissions and turnover soar as a result in these first few days of the year, the reader or taxpayer should be more concerned about these disastrous records...

Not only are the amounts much larger than in most previous years but borrowing costs have also soared in the meantime. For example, a new French government bond issue in 2018 cost the government between 0 and 1% in annual interest; today it costs between 2.5% and 3.8%, depending on its maturity. And given the budgetary balances, we can imagine that the France is more inclined to borrow on long maturities, and therefore the most expensive ones, than on 6-month maturities... Thus, between this massive increase in debt and its cost, the scissor effect is even more violent on public accounts and therefore on public deficits and future debt... The fatal mechanism seems hard to stop, especially when we hear analysts and other institutions debating their potential growth forecasts as to whether it will be closer to 1% or closer to 0%. .. As if the stakes were there, and as if this thick line could change the course of the Eurozone's main problem: its economic sluggishness, its impoverishment, its dependence on the outside world for its consumption, the weakening of its political and geopolitical status and of its currency, its difficulty in reforming itself and, as a corollary to all this, its debt trajectory in a straight line towards calvary...

The simple increase of 30% in the amounts borrowed over these first ten days of the year, i.e. 240 billion euros represent more than 2024 total issues, added to the increase in borrowing rates of around 300 basis points since the era of zero interest rates, which adds an annual burden of 7 billion euros to the European States budgets... And we are still January 10th...

On the other hand, you will read in many publications that demand for these new bonds is solid, that the appeal of European sovereign bonds is strong because of the intrinsic quality of the Zone and the more attractive yields, even their premium over other yields; in particular, the government credit premium has widened significantly compared with swap rates. And it is true that we have seen huge demand for recent issues. Italy, for example, collected 270 billion euros as buying indication of interest on its new bonds last Thursday for a 18 billion issues (i.e. 15 times oversubscribed), while Belgium saw its book order jump to 89 billion euros on its new 10-year bond, i.e. 13 times oversubscribed.

These figures are a sham, and here are a few tips on how to read between the lines:

-

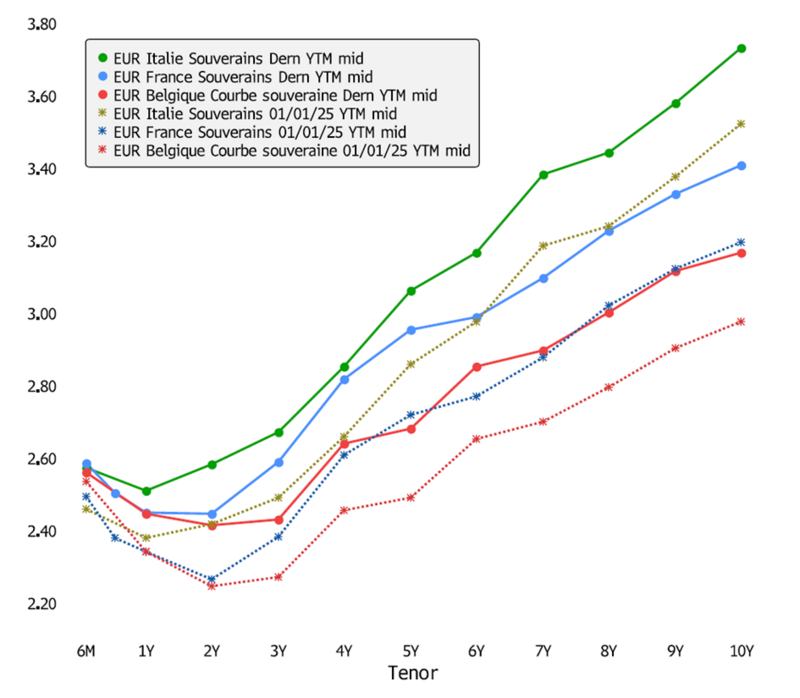

Net demand should not be confused with gross demand: in other words, these figures for the primary market are only valid if weighed against the figures for the secondary market. For example, many investors took positions on issues that have become too short and no longer match their target maturity, or wishing to capture a few basis points of premium, and sell bonds on the secondary market to acquire these new bonds. So, the only fair and definitive indication of the supply/demand balance in the sovereign bond market (as in any other market for that matter) is their price, and therefore their yield: if investor demand is stronger than the increase in the stock of bonds, then their price rises and the yield falls. Here are the yields for Italy, Belgium and France for all maturities since 1 January:

Sources (Bloomberg, Octo AM)

In short, they are all up, which means that bond prices have fallen and that net demand for the entire stock of government bonds, primary and secondary combined, is therefore down, contrary to what the spectacular figures for the primary market might lead you to believe. Demand on the primary market has therefore been more than offset by sales on the secondary market.

- So why this dichotomy and these flows of massive sales on the one hand and massive purchases on the other?

- Speculation: government bonds and the futures linked to them are extremely liquid instruments, because of the mass of debt on the market, allowing many traders to make quick trades for staggering amounts. If we take the example of the Italian bond issued this week, it was able to offer a premium of 5 basis points over secondary bonds at the time of issue in order to ‘attract customers’, as we would say in more concrete markets... Arbitrageurs, various traders from banking establishments and other trading funds then have a field day buying this new bond while selling the others on the secondary market in order to capture the premium without exposing themselves structurally to the market. Usually within a few hours for sovereign bonds and a few days for corporate bonds, this premium is reabsorbed because of this arbitrage game... a zero-sum game except for the speculator who will have captured his 0.05% gain.

- Position rolls: as we have often said, a large proportion of bond investments are made in line with indices, notably via benchmarked funds or ETFs. These indices are based on the amount of debt in circulation and track changes in the stock of debt. So, when a major new issue comes onto the market, their constituents are modified in favour of the new bond, to the detriment of a few others already in circulation, which is then done by all the investors following this index... Once again, a virtually zero-sum game, since these are simple reallocations which benefit the primary issue to the detriment of secondary bonds.

- Finally, some bond market participants and derivatives focus on the issues that are most characteristic of a sovereign. For example, futures focus on a few key maturities: 2-year, 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year, choosing the bond closest to these targets. So when Italy or Belgium issues a new 10-year bond, which they call a ‘benchmark’, many ‘mechanical’ players lose interest in the old 10-year bond already on the market, which has become a 9-year bond with a few months to run, and concentrate on this new bond that is closer to the precise 10-year maturity target corresponding to their model or derivative product. Once again, a zero-sum game from a fundamental point of view.

Sources (Bloomberg, Octo AM)

Ultimately, the only variable to look at in the sovereign bond market is the final interest rate, with the technical and operational aspects of this market creating visual effects if we focus on a particular point, primary or secondary market for example. This is quite different in the corporate bond market, where the intrinsic specificities (between underlying, subordinations, documentations) are more important, where the pool of bonds is much more limited, where the refinancing issue is more specific and more key in the financial strategy, and where the yield spreads between bonds are higher.

The only conclusion to be drawn about sovereign bonds at the moment is that interest rates are rising as a result of a sharp increase in their indebtedness and demand that is not keeping pace, penalised by the ECB's withdrawal from the game, investors' concerns about the European trajectory, and a gradual disinterest in the euro as a reserve currency from an international point of view. Therefore, we still limit the sovereign bond positions in our portfolios to almost zero, to maintain a shorter duration than our indices and avoid France, the Eurozone's worst performer in terms of debt and budget, whether in terms of its government bonds or financials, which are often closely linked to political risk in the event of major stress and which balance sheets are generally heavily loaded with bonds from their domiciliation country.